Range Creek, Utah, it was here about 700 years ago that a tribe of Indians called the Fremont, suddenly vanished so fast that they left arrows, arrow heads, tools and toys, scattered on the ground. They also abandoned a granary still holding corn and rye. Let's take a closer look...

Range Creek, Utah, it was here about 700 years ago that a tribe of Indians called the Fremont, suddenly vanished so fast that they left arrows, arrow heads, tools and toys, scattered on the ground. They also abandoned a granary still holding corn and rye. Let's take a closer look...

The disappearance of the Fremont Indians is one of North American archaeology's most enduring mysteries. The tribe, which prospered for over 600 years in the harsh terrain found between the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada, were adaptable and startlingly diverse. While some lived in semi-subterranean "pit houses," others made their homes in rock shelters. They farmed, and much evidence of corn and other crops were found but they also hunted and foraged for food. Yet despite their adaptability, things seemed to have come t an abrupt end for the Fremont around 1300 A.D. Fore around that time, their culture had all but vanished.

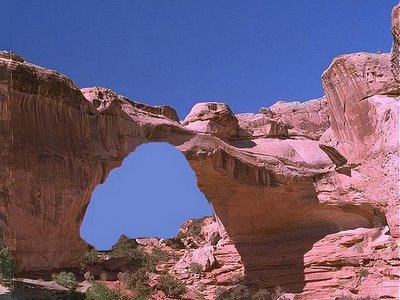

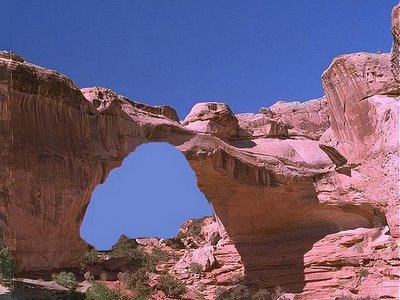

So, what became of them? The Range Creek site, unveiled in 2004, holds important clues. The ruins are not visually spectacular like those of the Anasazi, the Fremont's master-builder neighbors to the south. Still, Range Creek is astonishingly pristine and so should provide a rare window into the daily lives--and fears--of these early Americans.

Range Creek escaped both the intrusion of looters and the excavations of archaeologists thanks in large part to local rancher Waldo Wilcox, who owned and guarded the site for over half a century until 2001 when he sold it to the State of Utah for $2.5 million. Wilcox would often visit the many sites on the ranch but knew to leave it untouched, he both knew and respected what he found on his land. Perhaps more importantly he never told anyone about what he knew he had discovered on his land. But the inaccessibility of the sites also helped preserve the hundreds of ruins, sprawling across thousands of acres, 34 axle-crunching miles from the closest stretch of unbroken pavement, over a serpentine thriller of a mountain pass.

Researchers have just begun surveying the canyon, but already the ruins are raising tantalizing questions, says archaeologist Jerry Spangler, author of a recent book on the Fremont called Horned Snakes and Axle Grease. The stubby circular remains of some pit houses, for instance, are 30 feet in diameter, three times as large as the typical Fremont pit house. Archaeologists have long thought of the Fremont as simple farmers who lived in small family groups, says Spangler. But the Range Creek mini-mansions suggest that some lived with extended families or had strong enough bonds with other families to build communal structures for ceremonial or other purposes.

Range Creek may also reveal more about the relationship between the Anasazi and the Fremont, who have long suffered by comparison with them. Until now, it has been thought that the two groups didn't interact much. But at Range Creek, almost all the settlements are littered with Anasazi as well as Fremont pottery. Archaeologists aren't sure what to make of this mingling. One intriguing possibility, however, is that the two groups did, in fact, trade with each other and that evidence of these dealings was expunged from other Fremont ruins by early relic hunters who selectively stole the fancier Anasazi ceramics.

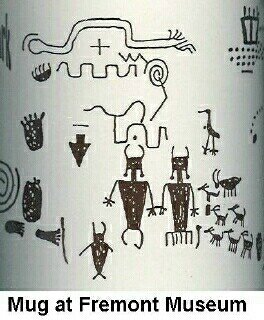

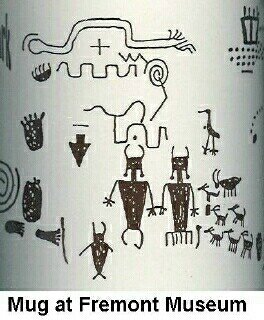

Like the Anasazi, the Fremont raised corn, beans, and squash, but they relied more heavily on wild foods, probably trekking every year between fields near creeks and rivers and foraging grounds. The Fremont left behind distinctive baskets, trapezoidal-shaped clay figurines, and rock art of unparalleled beauty and complexity. "The Anasazi have some interesting rock art," says Spangler, "but the Fremont were absolutely brilliant artists."

Like the Anasazi, the Fremont raised corn, beans, and squash, but they relied more heavily on wild foods, probably trekking every year between fields near creeks and rivers and foraging grounds. The Fremont left behind distinctive baskets, trapezoidal-shaped clay figurines, and rock art of unparalleled beauty and complexity. "The Anasazi have some interesting rock art," says Spangler, "but the Fremont were absolutely brilliant artists."

Although archaeologists are generally reluctant to read too much into rock art, some venture to say that panels in nearby Nine Mile Canyon may give clues as to the demise of the Fremont. "Some appear to depict warfare quite graphically," says Utah state archaeologist Kevin Jones. There are, for example, panels with images of people apparently wielding weapons and shields. Jones also sees evidence of strife in the little granaries tucked way up high into rock faces at Range Creek and the ruins of dwellings perched on pinnacles 900 feet above the canyon floor. "We've had to use technical climbing gear to get to some of these spots," he says.

What had the Fremont climbing the walls? Researchers are still piecing together the story, but the archaeological record shows that the Anasazi ran into trouble about the same time as the Fremont, suggesting, says Jones, "that something was occurring on a large scale across North America." One stress was undoubtedly a drought that began in A.D. 1270 and lasted 25 years. Another may have been the new groups--including ancestors of the Paiute and Ute peoples--moving into their arid territory, competing for plant and animal resources. "When people are starving and looking for ways to survive," says archaeologist David Madsen, author of Exploring the Fremont, "there's almost always violence."

Researchers already know how it all turned out: By the time Europeans arrived, the new crowd was in residence, and nearly all traces of the Fremont had disappeared. But what about the last act? Warfare and famine undoubtedly claimed many Fremont. But there's a debate about the fate of the rest of them. Shawn Carlyle, an adjunct professor of anthropology at the University of Utah, believes that, like the Anasazi, many Fremont picked up and moved south, where they became the historic Pueblo people. He has analyzed ancient DNA from Anasazi and Fremont skeletons and found that it is more closely related to DNA from modern-day Pueblos than that from Northern Paiutes.

Madsen also believes that the remnant Fremont moved on. "The sudden replacement of classic Fremont artifacts by different kinds of basketry, pottery, and art styles historically associated with Utah's contemporary native inhabitants suggests that Fremont peoples were for the most part pushed out of the region," he writes. Kevin Jones envisions a somewhat happier ending. He thinks some Fremont families survived on their lands by reverting to full-time hunting and gathering. "Imagine if one day you or I had to leave our homes and strike out on our own," he says. "A thousand years from now, it would look like we'd disappeared when, in fact, we were just doing something different."

Killed off by war and famine or just doing something different, either way it is an intriguing and dare I say somewhat weird mystery that, thanks to one rancher and the State of Utah, we may one day be able to solve. Keep walking this big weird would of ours! See you next time.

I’m Average Joe

Like the Anasazi, the

Like the Anasazi, the

No comments:

Post a Comment